Dan recently posted what has to be one of the most thorough/comprehensive blog articles regarding the

Dan recently posted what has to be one of the most thorough/comprehensive blog articles regarding the Windows shellbags artifacts. His post specifically focuses on shellbag artifacts from Windows 7, but the value of what he wrote goes far beyond just those artifacts.

Dan states at the very beginning of his post that his intention is to not focus on the structures themselves, but instead address the practical interpretation of the data itself. He does so, in part through thorough testing, as well as illustrating the output of two tools (one of which is commonly used and endorsed in various training courses) side-by-side.

Okay, so Dan has this blog post...so why I am I blogging about his blog post? First, I think that Dan's post...in both the general and specific sense...is extremely important. I'm writing this blog post because I honestly believe that Dan's post needs attention.

Second, I think that Dan's post is just the start. I opened a print preview of his post, and with the comments, it's 67 pages long. Yes, there's a lot of information in the post, and admittedly, the post is as long as it is in part due to the graphic images Dan includes in his post. But this post needs much more attention than "+1", "Like", and "Good job!" comments. Yes, a number of folks, including myself, have retweeted his announcement of the post, but like many others, we do this in order to get the word out. What has to happen now is that this needs to be reviewed, understood, and most importantly, discussed. Why? Because Dan's absolutely correct...there are some pretty significant misconceptions about these (and admittedly, other) artifacts. Writing about these artifacts online and in books, and discussing them in courses will only get an analyst so far. What happens very often after this is that the analyst goes back to their office and doesn't pursue the artifacts again for several weeks or months, and by the time that they do pursue them, there are still misconceptions about these artifacts.

Shell Items

This discussion goes far beyond simply shellbags, in part because the constituent data structures, the shell items, are much more pervasive on Windows systems that I think most analysts realize, and they're becoming more so with each new version. We've known for some time that Windows shortcut/LNK files can contain shell item ID lists, and with Windows 7, Jump Lists were found to include LNK structures. Shell items can also be found in a number of Registry values, as well, and the number of locations has increased between Vista to Windows 7, and again with Windows 8/8.1

Consider a recent innovation to the Bebloh malware...according to the linked article, the malware deletes itself when it's loaded in memory, and then waits for a shutdown signal, at which point it writes a Windows shortcut/LNK file for persistence. There's nothing in the article that discusses the content of the LNK file, but if it contains only a shell item ID list and no LinkInfo block (or if the two are not homogeneous), then analysts will need to understand shell items in order to retrieve data from the file.

This discussion goes far beyond simply shellbags, in part because the constituent data structures, the shell items, are much more pervasive on Windows systems that I think most analysts realize, and they're becoming more so with each new version. We've known for some time that Windows shortcut/LNK files can contain shell item ID lists, and with Windows 7, Jump Lists were found to include LNK structures. Shell items can also be found in a number of Registry values, as well, and the number of locations has increased between Vista to Windows 7, and again with Windows 8/8.1

Consider a recent innovation to the Bebloh malware...according to the linked article, the malware deletes itself when it's loaded in memory, and then waits for a shutdown signal, at which point it writes a Windows shortcut/LNK file for persistence. There's nothing in the article that discusses the content of the LNK file, but if it contains only a shell item ID list and no LinkInfo block (or if the two are not homogeneous), then analysts will need to understand shell items in order to retrieve data from the file.

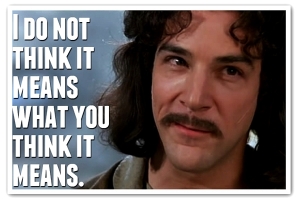

These artifacts specifically need to be discussed and understood to the point where an analyst sees them and stops in their tracks, knowing in the back of their mind that there's something very important about them, and that the modification date and time don't necessarily mean what they think. It would behoove analysts greatly to take the materials that they have available on these (and other) artifacts, put them into a format that is most easily referenced, keep it next to their workstation and share it with others.

Publishing Your Work

A very important aspect of Dan's post is that he did not simply sit back and assume that others, specifically tool authors and those who have provided background on data structures, have already done all the work. He started clean, by clearing out his own artifacts, and walking through a series of tests without assuming...well...anything. For example, he clearly pointed out in his post that the RegRipper shellbags.pl plugin does not parse type 0x52 shell items; the reason for this is that I have never seen one of these shell items, and if anyone else has, they haven't said anything. Dan then made his testing data available so that tools and analysis processes can be improved. The most important aspect of Dan's post is not the volume of testing he did...it's the fact that he pushed aside his own preconceptions, started clean, and provided not just the data he used, but a thorough (repeatable) write-up of what he did. This follows right in the footsteps of what others, such as David Cowen, Corey Harrell and Mari DeGrazia, have done to benefit the community at large.

A very important aspect of Dan's post is that he did not simply sit back and assume that others, specifically tool authors and those who have provided background on data structures, have already done all the work. He started clean, by clearing out his own artifacts, and walking through a series of tests without assuming...well...anything. For example, he clearly pointed out in his post that the RegRipper shellbags.pl plugin does not parse type 0x52 shell items; the reason for this is that I have never seen one of these shell items, and if anyone else has, they haven't said anything. Dan then made his testing data available so that tools and analysis processes can be improved. The most important aspect of Dan's post is not the volume of testing he did...it's the fact that he pushed aside his own preconceptions, started clean, and provided not just the data he used, but a thorough (repeatable) write-up of what he did. This follows right in the footsteps of what others, such as David Cowen, Corey Harrell and Mari DeGrazia, have done to benefit the community at large.

Post such as Dan's are very important, because very often artifacts don't mean what we may think they mean, and our (incorrect) interpretation of those artifacts can lead our examination in the wrong direction, resulting is the wrong answers being provided as a result of the analysis.