Within the DFIR and threat intel communities, there has been considerable talk about "TTPs" - tactics, techniques and procedures used by targeted threat actors. The most challenging aspect of this topic is that there's a great deal of discussion of "having TTPs" and "getting TTPs", but when you really look at something hard, it kind of becomes clear that you're gonna be left wondering, "where're the TTPs?" I'm still struggling a bit with this, and I'm sure others are, as well.

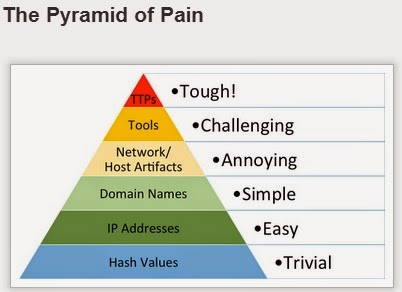

I ran across Jack Crook's blog post recently, and didn't see how just posting a comment to his article would do it justice. Jack's been sharing a lot of great stuff, and there's a lot of great stuff in this article, as well. I particularly like how Jack tied what he was looking at directly into the Pyramid of Pain, as discussed by David Bianco. That's something we don't see often enough...rather than going out and starting something from scratch, build on some of the great stuff that others have done. Jack does this very well, and it was great to see him using David's pyramid to illustrate his point.

A couple of posts that might be of interest in fleshing out Jack's thoughts are HowTo: Track Lateral Movement, and HowTo: Determine Program Execution.

More than anything else, I would suggest that the pyramid that David described can be seen as a indicator of the level of maturity of the IR capability within an organization. What this means is that the more you've moved up the pyramid (Jack provides a great walk-through of moving up the pyramid), the more mature your activity tends to be, and when you've matured to the point where you're focused on TTPs, you're actually using a process, rather than simply looking for specific data points. And because you have a process, you're going to be able to not only detect and respond to other threats that use different TTPs, but you'll also be able to detect when those TTPs change. Remember, when it comes to these targeted threats, you're not dealing with malware that simply does what it does, really fast and over and over again. Your adversary can think and change what they do, responding to any perceived stimulus.

Consider the use of PSExec (a tool) as means to implement lateral movement. If you're looking for hashes, you may miss it...all someone has to do is flip a single bit within the PE file itself, particularly one that has no consequence on the function of the executable, and your detection method has been obviated. If a different tool (there are a number of variants...) is used, and you're looking for specific tools, then similarly, your detection method is obviated. However, if your organization has a policy that such tools will not be used, and it's enforced, and you're looking for Service Control Manager event records (in the System Event Log) with event ID 7045 (indicating that a service was installed), you're likely to detect the use of the tool on the destination systems, as well as the use of other similar tools. In the case of more recent versions of Windows, you can then look at other event records in order to determine the originating system for the lateral movement.

Book

Looking for Service Control Manager/7045 events is one of the items listed on the malware detection checklist that goes along with chapter 6 of Windows Forensic Analysis, 4/e.

Looking for Service Control Manager/7045 events is one of the items listed on the malware detection checklist that goes along with chapter 6 of Windows Forensic Analysis, 4/e.

When it comes to malware, I would agree with Jake's blog post regarding not uploading malware/tools that you've found to VT, but I would also suggest that the statement, "...they create a new piece of malware, with a unique hash, just for you..." falls short of the bigger issue. If you're focused on hashes, and specific tools/malware, yes, the bad guy making changes is going to have a huge impact on your ability to detect what they're doing. After all, flipping a single bit somewhere in the file that does not affect the executionof the program is sufficient to change the hash. However, if you're focused on TTPs, your protection and detection process will likely sweep up those changes, as well. I get it that the focus of Jake's blog post is to make the information more digestible, but I would also suggest that the bar needs to be raised.

Uploading to VT

One issue not mentioned in Jake's post is that if you upload a sample that you found on your infrastructure, you run the risk of not only letting the bad guy know that his stuff has been detected, but more than once responders have seen malware samples include infrastructure-specific information (domains, network paths, credentials, etc.) - uploading that sample exposes the information to the world. I would strongly suggest that before you even consider uploading something (sample, hash) to VT, you invest some time in collecting additional artifacts about the malware itself, either though your own internal resources or through the assistance of experts that you've partnered with.

One issue not mentioned in Jake's post is that if you upload a sample that you found on your infrastructure, you run the risk of not only letting the bad guy know that his stuff has been detected, but more than once responders have seen malware samples include infrastructure-specific information (domains, network paths, credentials, etc.) - uploading that sample exposes the information to the world. I would strongly suggest that before you even consider uploading something (sample, hash) to VT, you invest some time in collecting additional artifacts about the malware itself, either though your own internal resources or through the assistance of experts that you've partnered with.

A down-side of this pyramid approach, if you're a consultant (third-party responder), is that if you're responding to a client that hasn't engineered their infrastructure to help them detect TTPs, then what you've got left is the lower levels of the pyramid...you can't change the data that you've got available to you. Of course, your final report should make suitable recommendations as to how the client might improve their posture for responding. One example might be to ensure that systems are configured to audit at a certain level, such as Audit Other Object Access - by default, this isn't configured. This would allow for scanning (via the network, or via a SIEM) for event ID 4698 records, indicating that a scheduled task was created. Scanning for these, and filtering out the known-good scheduled tasks within your infrastructure would allow for this TTP to be detected.

For a good example of changes in TTPs, take a look at this CrowdStrike video that I found out about via Twitter, thanks to Wendi Rafferty. The speakers do a very good job of describing changes in TTPs. One thing from the video, however...I wouldn't think that a "new approach" to forensics is required, per se, at least not for response teams that are organic to an organization. As a consultant, I don't often see organizations that have enabled WMI logging, as recommended in the video, so it's more a matter of a combination of having an established relationship with your client (minimize response time, maximize available data), and having a detailed and thorough analysis process.

Regarding TTPs, Ran2 says in this EspionageWare blog post, "Out of these three layers, TTP carries the highest intelligent value to identify the human attackers." While being the most valuable, they also seem to be the hardest to acquire and pin down.